Rick's b.log - 2014/11/23

You are 18.119.106.149, pleased to meet you!

Rick's b.log - 2014/11/23 |

|

| It is the 18th of December 2024 You are 18.119.106.149, pleased to meet you! |

|

mailto: blog -at- heyrick -dot- eu

This is the baby of the family - barely larger than my hand. Here is an "epic angle" shot to make it look a lot larger than it really is.

From an engineering point of view, it is quite a marvel. It may be a mere toy, but to create a functional helicopter in this sort of size is quite astonishing. Here is a photo of the insides, and you can see the battery looks and feels like an electrolytic capacitor, while the motor appears to be about the same sort of size as the tiny surface-mount chip. Yup, that's one of the drive motors, this one powering the lower blade.

There are three motors, as in most helicopters of this design. One for the upper blades, one for the lower blades, and one - even dinkier - for the tail blade. Here's a photo of the tail blade motor next to a tripe-A (AAA) cell.

The basic operation of flight is quite simple. A rotor turns which pushes air down. The air forced down causes the craft to rise. In a real helicopter, you normally only have one set of blades on top, either two or four depending upon aircraft type. If this was all you had, the helicopter would just spin and spin until it crashed. Here is a YouTube video of a helicopter not surviving a tail rotor failure.

And, well, that's basically it.

I only flew this helicopter a couple of times, as with my first craft, wind is a problem. Because this model is so tiny, slight breezes are a problem. However, the one thing that insantly stood out for me is the behaviour of the "gyro". Unlike my original helicopter, this one contains a little device inside to keep the tail steady. If you recall from my previous videos, I spent forever trying to trim the settings of my original model to attempt to keep it steady, however as the battery was used, it would affect the relative speeds of the motors so the model would begin to spin again. Not so here, the micro helicopter rises up and the tail stays put. If it does drift, there is a control to trim that out, but most of the drifting is the breeze pushing the craft around, not the craft itself. My original helicopter was damn near unflyable thanks to its lack of a gyro. This, as cheap and silly as it might seem, offers a better flight experience right from throttle up.

It is, and I cannot stress this enough, absolutely at the whim of the elements. Just now I went into the attic over the cow barn. There was still some breeze inside as the wind (quite strong now) could come in under the bottom of the roof - it's a cow ban, it isn't supposed to be sealed. That said, apart from some (a fair bit of) drift, I could turn the craft and make it go forwards and backwards. Easily the best, and most controlled, flight I have ever had with a model helicopter. It also seems to me as if the flight time lasted longer than normal, like maybe 12 or so minutes? That's quite good when you consider the original helicopter managed maybe seven or so.

I ought to say it just in case somebody asks - no, I don't have plans to attach a camera to this. Its lifting capacity might stretch to an SD card or two. That's about it.

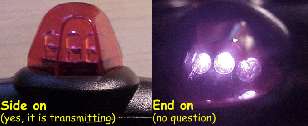

Something to keep in mind is that the model is controlled by infra-red, not radio. For this reason, the top of the controller should always point towards the model. This will give the brightest signal to the receiver. Don't hold the controller upright as some people do for radio control models. Here is why:

To wrap up, I handed the controls over to mom and recorded the result. She does not know much about flying the helicopter, she controlled the up and down, and the breeze did the rest. The crash at the end was most likely due to the helicopter losing sight of the controller's signals. You can see, even in wind, that the inexpensive "gyro" works hard to keep the craft steady.

Micro helicopter

So I was looking around the end-of-line-or-reject-stuff shop the other day when I saw a little model helicopter for... what was it, six or seven euros? Cheap enough to have some fun with. It was probably here because the USB charging lead was missing. My box hadn't been tampered with, perhaps an incorrect batch? This wasn't critical as the remote controller has a built-in charger too.

Proper helicopters and large scale models control direction and acceleration by altering the pitch of the blades in clever ways. A small inexpensive model cannot possibly handle mechanics of that nature. So they use an alternative method of flight.

Namely, two rotors, one above the other.

The rotors are controlled by independent motors, and they rotate in opposite directions. This immediately deals with the spinning problem, as two rotors providing equal rotation in opposite direction will cancel each other out. It also throws in steering for free, for if you want to turn the aircraft one way or the other, you just slightly slow one of the rotors to cause the craft to spin. When it has turned to where you want, the rotor speeds up and the spinning stops.

You still need a tail rotor, but it is no longer essential for flight safety. Indeed, in most of these model helicopters, the craft will take flight with the tail rotor stationary. You will notice from the photo above that the tail is horizontal, unlike a real helicopter. This is because the tail is used for forwards and backwards movement. The rotor is tiny as it doesn't actually need to do much - by spinning and moving air, the little rotor will either push the tail down or raise it up. The effect of this is to throw the helicopter's centre of gravity off balance, so instead of hovering, it will begin to move forward (tail up) or backward (tail down).

David Pilling, 26th November 2014, 02:56

| © 2014 Rick Murray |

This web page is licenced for your personal, private, non-commercial use only. No automated processing by advertising systems is permitted. RIPA notice: No consent is given for interception of page transmission. |