Rick's b.log - 2015/08/10

You are 3.135.247.17, pleased to meet you!

Rick's b.log - 2015/08/10 |

|

| It is the 24th of November 2024 You are 3.135.247.17, pleased to meet you! |

|

mailto: blog -at- heyrick -dot- eu

Really? Here's the first line of the Lord's Prayer that most people today would understand (even if it reads like it is aimed at attention-span-deficit five-year-olds):

Most British people who went anywhere near a traditional CofE church would probably know this one:

Which means, working back, the Lord's Prayer in 1600 would look sort of like a poncey form of English, while the same in 1400, say, would look quite different.

A quick deviation - if you come across any Jehovah's Witnesses that insist that God's real name is Jehovah (wait - isn't his real name supposed to be unknown to us?), you might want to point out that the sound that we know as 'J' first turned up in Germanic languages around 1450 or so, and it took around two centuries for the concept of 'J' to make it to English. Prior, and even sometimes today, the 'j' sound is a 'y'. Think of the island of "ma-yor-ka" (spelled with a 'j' in English and a double 'l' in Spanish). As such, it is not so much the true name of God as it is an attempt to say "YHWH" with modern linguistics.

Anyway, back to the prayer. What you saw above was Middle English. Here is Old English (proper Old English, not the affected "olde englishe" that is a bastardised non-serious version of Shakespearean writing) from around 1000AD:

This is Beowulf. Our language, a thousand years ago. Good luck.

Prior to the Anglo-Saxons? We'd be going back in time to the end of the Roman era, when people would have spoken Latin. Before them? A Celtic language often referred to as "Brittonic" (despite being several related languages), which - in keeping with modern Celtic/Gaelic - had a lot on common with Gaulish spoken by people in what is now France, which isn't a surprise as related forms of the Celtic language were spoken across many parts of central Europe, from the British Isles to Asia Minor (modern day Turkey, down to Syria). Most traces of this have been lost, however there are a few reminders lingering - for example the River Thames is thought to have derived from Tamesis meaning "dark" (and explains the "Th as a hard T" better than some rubbish about a king with a lisp). It would also explain the Oxford section, commonly known as Isis as simply being the end of the Brittonic word.

So........I have demonstrated that the language spoken in the United Kingdom changed a little bit up to around 400 years ago, and radically/wildly somewhat frequently before that. With that in mind, you tell me how anybody could go back in time by any appreciable span and be understood.

That said, the English language is evolving. I started boarding school in 1985 and finished in 1990 and I shall give you a sentence that would make sense to a modern geek but would mean nothing at all back then:

Or, the version that would be understood by Gene Hunt or a 12 year old Rick:

Haters, blog, sexting, texts, tweet, muggle, google, mashup, web, browser, netbook, tablet, mobile... just some words that either didn't exist in the '80s or had a different meaning. A text probably referred to a dry textbook, tweet is what a bird did, web was something Charlotte constructed, I suppose people that browsed continually might have been nicknamed browsers, a tablet was a sort of medicine (or a slab of rock with words carved upon), and a mobile was a thing you hung above a cot or part of a fancy phrase for a caravan.

Language evolves

You know the thing that really bugs me? When movie time travellers go back in time and maybe if you are lucky they will take special care not to present anachronisms of modern day, like going back to Roman Times and wearing digital watches. Yet, mysteriously, they will be able to communicate effortlessly with the locals.

Our Father, who is in heaven, may your name be kept holy.

Our father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name.

This one is interesting. Dating from around 1600AD, Early Modern English looks a lot like something we would understand, but it didn't sound like it. For example, the idiosyncratic "name" (silent 'e') derives from the fact that the word was originally said like "na-meh" ('a' as in father), then as "na-meh" ('a' as in cat), then as "ne-meh" ('e' as in bed), then like "nay-meh" ('ay' as in play), and finally a minor change of vowel but the two halves were joined to be the word "name" we know today, the final 'e' becoming silent. All of this happened mostly between 1400 and 1700 and, really, it is a wonder anybody understood anybody else.

Correct.

Oure fadir that art in heuenes halowid be thi name,

This version, from 1400, still sort of sounds like English if you read it aloud.

Faeder ure thu the eart on heofonum, si thin nama gehalgod

Here we can see name is spelled as "nama"... and the rest looks like English mixed with some sort of Germanic language. That is exactly what it is. The language of the Anglo-Saxons that was in use from around 500AD until the Norman Invasion in 1066AD (which brought French as the court language). Even then, the languag wasn't fixed, and it is believed that early versions were written in runes rather than the Latin characters we know today. Little remains of the early form of this language, though we do have a good example of the later Old English in the form of the poem "Beowulf".

One I like is the River Avon, which derives from abonā, which means "river". So, yeah, running through Bristol is the River called River.

I left my netbook on overnight to torrent Pixar's latest. I'll need to wiki it, or just google it, to see if it's worth bothering with or if I should chuck it on the NAS where it can be forgotten about.

I left my

netbook on overnight to torrent Pixar's latest. I'll need to wiki it, or just google it, to see if it's worth bothering with or if I should chuck it on the NAS where it can be forgotten about.Skills we are losing

The Ordnance Survey conducted a test with 2000 British people and discovered that map reading is the number one skill we have lost. Well, gee, are we surprised?

Becoming lost to the skill of being able to operate a sat-nav and attempting to be intelligent enough that if she (for it is often a female voice) says "TURN LEFT!", you don't if it means cutting into high speed oncoming traffic, ploughing through a barrier, and ending upside down in a lake.

My mother claims she taught me how to read a map. I actually knew beforehand, but I much prefer to use Google Maps because the map books... can be economical with the truth.

No, no, and no again.

It's a French town. So you know there is probably going to be a church in the middle, the road passing around it. And some other buildings. The roads themselves will be offset by a quarter of a kilometre, hidden behind buildings, camouflaged by a one-way system that only makes sense if you're whacked out on drugs, and the roads are all helpfully marked by road signs that either face every direction except from where you are coming, or are the very typical French arrangement of having signs arbitrarily pointing "sort of" the right direction but enough to leave it ambiguous.

La Boissière-du-Doré looks like a crossroads, right? Here's reality:

As far as reading a map is concerned, the top is North. Don't be afraid to do it girl-style and rotate the book so you're holding it to face the way you're going. There is no shame in that, it is exactly what Google's Navigation does.

One thing my mother did teach me - if you are coming up to a junction and you want the driver to follow a road, don't give the name of the first town you see. Follow the road along and look for two things - the road number and the big town that it goes to. Quite a few roads around here will say useful things like "Laval" or "Angers" despite the fact that Laval/Angers isn't directly on that road, is thirty-some kilometres away, and there are half a dozen towns before then. But, Laval/Angers is the big town so it gets named. The little ones don't.

A 'real' compass is just like the apps you can download for your phone, except generally the coloured part points North. Most modern mobile phones point anywhere until you "calibrate" them by waving them around in a figure of eight and make yourself look a bit loony.

If you aren't sure, or you believe your compass is maybe a bit weird in some way, then the sun rises in the East and sets in the West (unless you are John Wayne in the movie The Green Berets). These are variable as the position of the sun rise/set changes through the seasons. One thing that is constant is that in the Northern Hemisphere, the sun is due south at noon UTC (not local time); or due north for the Southern Hemisphere.

Tying your laces, trying a slip knot (easy to undo), and tying a tie - those are the three important ones that will see you through life. If you want to be an acrobat of knot tying, become a fisherman.

I curse my darn socks every time they aren't where I left them.

Seriously - a spool of thread and neelde ... neelde? Am I speaking Old English now? Right... A spool of thread and a needle pack will cost around €10; an inexpensive 3-pack socks is around €4. I might regret not having the ability to darn socks (or find my darn socks) after the Zombie Apocalypse, but for now it's easier just to go buy a new pack. It might work out slightly more expensive in the long run, but one repair kit equals about 10 socks.

First, find a book. So many libraries turning into "media centres", it is depressing. Especially as libraries tended to be staffed by a combination of failed history teachers and really cute girls.

Let's say you want to find the chemical drawing of caffeine. Well, it is a stimulant so I guess you might want to look at organic chemisty, medicine - drugs, maybe food and drink - coffee. Browse the shelves, look for books that may be of interest. Take them down, turn to the back. The long list of words with page numbers. Nothing for caffeine? Try another book. And another. You ought to find it eventually.

Or you can, you know, look up more information than any sane person ever needs to know about caffeine on Wikipedia in about...oh...seventeen seconds.

Don't think I'm too modern though. When I am talking about ARM programming, I frequently use the old style (pre-UAL) names for the instructions. Why? Easy. The latest ARM documents are all PDFs. I have on my phone and iPad the guide to the ARMv7 instruction set, the Cortex-A8, blah de blah. But when I need to look up stuff, I turn to the printed ARM ARM first. Here it is on my desk. It describes the ARMv5 instruction set, early VFP, and is fifteen years old. But, look, it's as thick as a phone book. It contains exactly the same sort of information as a PDF, but there's just something more reliable about a printed book. Something that I just don't feel from a PDF.

Being in a school for people with learning difficulties, this is something we didn't cover. That said, reading the sorts of things that happen now, I wonder if a correct letter ought not begin with Oi, you incompetent twat and end with I expect swift corrective action. and none of the formal niceness that you used to use. Writing to your bank manager? Hah - it's a computer that makes the decisions these days, and it is a computer programmed to believe you are a liar, and it is a distrustful computer with data entered by a bored graduate wondering why he is doing this crap and not wearing Armani suits and siphoning money out of hedge funds. In other words, you could write your letter in Romaji (or just Romanian) and you'd probably receive the same non-response from the bank... Or supermarket. Or...

...only necessary because the British would rather cling to an outmoded and batpoop-crazy French measuring system than to accept a modern sort-of-logical French measuring system. I have no idea what pounds and ounces are. A kilogram is a bag of flour. 280g is a ready meal.

Hopefully I do, mostly. This is written in a text editor. Not a word processor. Think "Notepad without the bugs". There's no spell check, certainly no grammatical check. Nothing like that.

How did I get to spell well when half the class had some form of dyslexia? Easy - I didn't learn at school. I read. I read John Whyndams when I was at junior school and other kids had big text with a picture on every facing page. Mom got me Robber Hopsika which was...kind of weird. She tried me with some Tolkien (I forget which) but I thought it a bit dumb. Rikki-Tikki-Tavi was the adventure of a mongoose - which for a long time I thought was some sort of bird until mom got me to look it up in an encyclopaedia. She, an avid reader herself, would often ask me questions based upon the stories that I have read, so there was no "yeah, read that" and not being bothered. For a long time there was not a lot worth watching on TV except the perennial battle between Saturday Swapshop and Tiswas, so I read. A lot.

This came to a crashing halt at boarding school. There was a library. Prefects only. With books bound in leather that don't look like anybody had read them in that century. I used to get frustrated at the pace of reading in lesson, so I'd beg/borrow/steal the books from the classroom. One of my favourites, Empty World, is a short book that I read from cover to cover while the lesser abled readers were struggling to get through the first chapter.

I can say with no hesitation that I'd rather experiment with setting parts of my anatomy on fire than have to endure Of Mice And Men again, and I never did make it though that horribly dreary book about the old guy and that bloody whale. Shakespeare is an acquired taste (and not one I'm fond of) and Jenny Nimmo rocks. At some point I probably read all of the Famous Five and Secret Seven, though the ... of Adventure series was the best. I also read ... at St. Clares and Mallory Towers and either that is a highly romanticised version of boarding school life, or a girl's school is very different to a boy's school. I think truth would be more like a cross between St. Trinians and if.... - but then, maybe I'm misremembering a romanticised version that was more interesting than it really was?

Irrelevant entry - why is this not categorised with entry #7?

Sunny day? Piece of wood and a magnifying glass. Sometimes field/forest fires start this way, with a discarded bottle being the magnifier when the sun is in the right place.

Cloudy day? Some dry tinder (wood shavings) and apparently twisting a piece of wood in a hole repeatedly with a makeshift bow or spinning it with your hands - though I never ever got that to work.

Rainy day? Much harder.

It's 2015. I have a lighter. I don't smoke, but I keep a lighter in case some fire is needed. It doesn't hurt to be prepared.

Oh my God! Enough with the "imperial" measurements already. Three entries? This is either subtle brainwashing or some sort of stupidity.

Done that. Boring as hell. It is probably more of a girl thing. I had enough trouble being taken seriously asking about cooking lessons, so...

I remember the home phone number. I call mom when I'm on break at work.

The one I don't remember is my own - I never call myself now, do I?

Isn't this just an extension of #15? Yeah, I understand that programming the number into electronic address books means you never have to dial it - but then there are still such things as actual phones with actual buttons. If you use one of those, it might be useful to remember the most important numbers? I guess it comes down to necessity - if your way of calling is tapping on Phone, swiping to Contacts, then finding the right face, you'll never know that person's number.

However, that said, you should learn the number of an important contact. You break down. Alone. It's a dark and stormy night. Your phone says No Signal. There's a gothic mansion just back a ways...you know how the story goes. Lots of dancing gay people and insanity that wouldn't be believed by one single psychiatrist in the land. So best to know your contact's phone number and where you last saw a public phone box. Better to get soaked in the rain than... well... the innocent passer by rarely turns out well in those sorts of movies...

Trees. Big and "epic"? Probably an Oak.

Tall and thin? Poplar.

Tall and impenetrable? Probably a Leylandii.

Looks like a Christmas tree? Some sort of generic pine.

Leaves like the flag of Canada? A Maple.

A sort of spindly Oak with leaves that have a lot of ribbing? Probably an Elm.

Silvery-white bark? Birch.

Looks a bit like an Oak but with serrated ribbed leaves? Try Beech.

For more precise identification and more trees, read this.

Flowers. You'll need a book. Some, like Daisy and Dandelion everybody knows. Others, like the Cow Parsley (Wild Chervil) look a little too much like Poison Hemlock. There's a clue in the name, and yes, it does kill people.

Insects? Ladybirds are cute beetles. Bumble bees are cute bees. Everything else in the insect world is less attractive and usually less desired, although some do good by killing others (Ladybirds eat aphids, for instance). Bees won't sting until they have to (it kills them). Wasps will sting if agitated. Hornets (giant wasps) sting for the lulz. Asian hornets (giant hornets) are worse, they want world domination. Insects? You're better off avoiding them, it's a harsh harsh world.

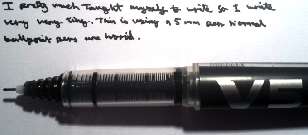

I don't suppose you have to be a good typist to tweet. However, proficient use of a keyboard allows you to get your ideas into a tangible form. I'm not a particularly quick typer, but fast enough that writing blog articles (like this one) is pleasurable. To communicate, share ideas, if you type really slowly (and can't write...) then surely you are closing yourself off from the world?

Easy. Open bag. Empty contents into tub. Add measured amount of lukewarm water. Close lid. Select white bread, lightly cooked. Press Start.

Seriously, if we're talking cake then I'm on board. Self-raising flour, sugar, eggs, butter, the whole deal.

Bread is a bit meh. All that bother with yeast, proving, kneading... Cake is just better.

Another girl-thing. In the Zombie Apocalypse, you won't care if your trousers are wrong (just turn 'em up), you'll be happy to be alive.

In the absence of girlfriend/wife/mother, turn to Google...

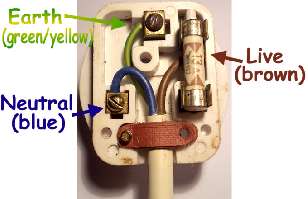

Ah, a non-girl thing. ☺ Okay, the standard British plug has a top that unscrews (or slides off). Open it up. You will see at the bottom some sort of cable clip to hold the cable securely. You must use this, as British plugs don't easily fall out of the socket like European and American plugs. Instead, you risk wrenching the cable out if you trip or snag it.

You will also see three copper pins with screws. If you look below the screws you will see holes. The idea is you loosen the screw, poke the wire in, and then tighten up the screw to hold the wire in place.

So. Lay your cable in place and remove the outer sheath so you can see the inner wires (it may help to clamp the cable at this point). There will be two or three of them. The brown goes to the screw-hole that connects to the fuse. This is called live. The blue goes to the screw-hole on the opposite side. This is called neutral. If you have a green and yellow wire, this goes to the screw-hole at the top. This is called earth.

NEVER EVER mix up Live (Brown) and Earth (Green/Yellow) as the outsides of many things (microwaves, fridges, etc) are often tied to earth - this is for your protection, but if the socket is incorrectly wired you risk making the device Live. That would be a very bad thing.

Now arrange the inner wires so they reach the terminals, and accounting for how much needs to go into each terminal, clip off the excess. On British plugs, the terminals are in different places so the wires will be different lengths.

Now strip off about 6mm (a quarter inch in old ways) of the insulation of each wire. If you don't have a wire stripper tool, you can do this by pressing gently with a craft knife (gently! don't cut the copper wires inside) and then pulling the insulation away with a pair of pliers. This should leave some shiny copper wires exposed.

Loosen the screws so the terminals are open. Insert the wires. Tighten up the screws.

Ensure no bare wires are in danger of touching each other or coming loose.

Check again - brown to the fuse, blue to the one opposite the fuse, and yellow/green to the top (longer) pin? Yes?

Then you're done. Put the top back on the plug. Job complete.

Rick's alternative list of skills we are losing

Like, say, a chicken or a piece of lamb.

Tomatoes? They aren't hard to grow and don't attract pests anything like the brassica family (that's broccoli and cabbage-like things). Potatoes? Herbs? Carrots?

Berries. Apples. Sugar. Boiling water. And a bit of magic.

The prevalence of "managed" engines means that all but simple repairs are now difficult. How many younger men would be able to strip down an engine?

Looking at all these "teach kids to code", it is all fairly high level stuff. It might be a quick way to get results, but knowing Ruby and Python makes you a web developer, not a programmer, and neither will teach you what actually goes on inside the machine. The worlds of assembly language, each one different, will blow your mind if you're used to the scripted stuff.

I reach for mine as I'm number dyslexic, however when I can add up something faster than a checkout girl and without using a calculator, it is clear that something is going horribly horribly wrong. I'm a dunce at maths, anybody worse than me... wow.

I'm as guilty of staring at my phone as everybody else. But then I'm a borderline-antisocial introvert. However it is strange to see a room full of people all looking at their Facebook message feeds. When one person talks, there is a brief moment where everybody acts as if somebody just took a dump on the floor. Then a few people will talk. Then they will go back to looking at their phones. I don't believe everybody is an introvert. They just find the world inside their smartphone to be more exciting than the world around them.

More specifically, while it is nice that some things include a GPS location, don't assume that we all have a GPS location. Obviously we all do as it covers planet Earth, however where I live right now? It has an address. A building on a road near a village near a town in a county in a country in a continent on a planet.

Okay, okay, you really want my GPS location? Fine. Suit yourself. Here you go: 23°49'54.2"N 46°23'26.8"W

I don't mean bolting together something from Ikea.

I mean buying some pieces of wood and making something, even if it is yet another birdhouse, maybe you'd branch out to a picnic table? The easy part of carpentry is the assembly. The medium-hard part is the cutting the pieces of wood. The hard part is working out what you want and the pieces of wood that can make it happen. It is a design. From a concept in your head, though to the implementation, and finally the finished article. Something you created yourself. Not something mass-produced that you self-assembled.

From our houses to our cars to the offices and back, we barely get our shoes wet even in winter. So it comes as no surprise that many Western civilisation people can't predict the weather any more, and when they need to know they look on the TV, they look in the newspaper, they check AccuWeather. None of that is reliable.

In countries where people get wet in the rain, or their food sources die if the weather is unfavourable, people are far more attuned to the caprices of the weather. Sure, it can surprise them, but I bet they could give a better forecast than any number of media sources. Because, freaky weather aside, weather does not "happen", it evolves. Cold air on a hot day can lead to thunderstorms. You can see these things building. Further back? Attuned people might be able to sense the wind changing, or the humidity, where we modern people let it all pass us by.

For what it is worth, Accuweather's iOS app tells me that right now I am having a thunderstorm. One is probably coming, the weather feels heavy. But right now? Right now, at half past midnight, I stepped outside and took a photo. It's a long (4 second) exposure on an inexpensive digital camera. I have modified the light and dark tones to make it more obvious (and more like I see, as opposed to a CCD imager).

Gavin Wraith, 12th August 2015, 12:52

I found that "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" becomes much more intelligible with knowing a bit of Danish. After all, as you go back in time the languages converge.

I used to darn my socks. Never learned to knit, though there was a boy at school who did.

This was an interesting whale of a blog.Rob, 25th August 2015, 13:20

Plugs ... that's an old one in the pic, Rick! There is some legislation now (in the UK anyway) that requires all appliances to come with a fitted plug, so having to put your own on almost never happens these days. Maybe should replace this with "choosing the right type of fuse" to go in it.Rob, 25th August 2015, 13:21

Plugs ... that's an old one in the pic, Rick! There is some legislation now (in the UK anyway) that requires all appliances to come with a fitted plug, so having to put your own on almost never happens these days. Maybe should replace this with "choosing the right type of fuse" to go in it.Rick, 25th August 2015, 17:50

God (or other nonexistent supreme being or your choice) got their own back - French plugs don't have fuses.

But on the flip side there is no "ring main" either.

| © 2015 Rick Murray |

This web page is licenced for your personal, private, non-commercial use only. No automated processing by advertising systems is permitted. RIPA notice: No consent is given for interception of page transmission. |